2 Men [Constantine + Hillel] ÷ 2 Agendas = 1 Massive Deception

| In the fourth century C.E., the ancient Sabbath was supplanted by Saturday through a change in calendars. The true Sabbath of Scripture was lost. |

One of the greatest frauds in the history of the world was perpetrated almost 1,700 years ago by the actions of two men. The Roman emperor, Constantine, committed a portentous act: he unified his empire by promoting Sunday as the day of Yahusha’s resurrection and outlawed the use of the Biblical calendar for calculating Passover. This set in motion a series of reactions. Jewish leader Hillel II responded to the persecution following this legislation by a modification of the Biblical calendar. This supplanted the true Sabbath with the pagan Saturday. It was a chain of actions and reactions of epic proportions. The ramifications continue to this day with every Christian and Jew that worships by the Gregorian calendar.

ACTION

Constantine

The fourth century was a vast sea change in the tumultuous ocean current of history. Christianity was gaining an ever-larger presence in the Roman Empire, while paganism remained the dominating influence. The time was ripe for someone with the power and initiative to take advantage of a unique time in history.

St. Constantine the Great (c. 272 – 337 C.E.) is widely viewed as the first “Christian” emperor of the Roman Empire. The reality is he was, first and foremost, a pagan. He allowed himself to be baptized shortly before his death, but he retained his position as head of the state religion and carried its title, Pontifex Maximus, until his death.[1] Even Catholics admit Constantine retained the office of pontifex maximus after his so-called “conversion.”[2]

Constantine was also a brilliant strategist with a political agenda. He wanted to unite the two most influential factions in his empire: pagans and Christians. Jews were a despised minority whose influence was to be contained and marginalized. Thus, Constantine’s efforts to unite his empire focused on finding a common ground to unite the pagans and western, paganized Christians. He found this in Sunday of the pagan, planetary week.

The early Julian calendar, like that of the Roman Republic before it, had an eight-day week. The letters A through H represented the days of the week. At that time, different countries used different means of keeping track of time and within the Roman Empire itself, there were regional differences in the Julian calendar. The pagan seven-day planetary week came to Rome in the first century B.C.E.[3]

Despite the emergence of the planetary week, the early Julian calendar continued to use an eight-day week for some time. “The nundinal [eight-day] cycle was eventually replaced by the modern seven-day week, which first came into use in Italy during the early imperial period,[4] after the Julian calendar had come into effect in 45 BC. The system of nundinal letters was also adapted for the [seven-day] week…. For a while, the week and the nundinal cycle coexisted, but by the time the week was officially adopted by Constantine in AD 321, the nundinal cycle had fallen out of use.”[5] While the pagan planetary week of seven days was known by the Romans and used regionally, the Julian calendar in use during and immediately following the life of Yahusha, still used an eight-day week.

This fact is supported by archeological evidence: the Julian fasti still in existence today show either eight-day weeks or list both eight-day and seven-day weeks on the same calendar.

The decline of the eight-day week coincided with the expansion of Rome. . . . The astrological [planetary] and Christian seven-day weeks that had just been introduced into Rome were also becoming increasingly popular. There is evidence indicating that the Roman eight-day week and those two seven-day cycles were used simultaneously for some time. However, the coexistence of two weekly rhythms that were entirely out of phase with one another obviously could not be sustained for long. One of them clearly had to give way. As we all know, it was the eight-day week that soon disappeared from the pages of history forever.[6]

This was not an immediate transformation. As the seven-day planetary week became more popular, the use of the letters (A through G) to designate days was laid aside and the days of the week were named after the planetary gods.

It is not to be doubted that the diffusion of the Iranian [Persian] mysteries has had a considerable part in the general adoption, by the pagans, of the week with the Sunday as a holy day. The names which we employ, unawares, for the other six days, came into use at the same time that Mithraism won its followers in the provinces in the West, and one is not rash in establishing a relation of coincidence between its triumph and that concomitant phenomenon.[7]

Archeological evidence shows Christians double dating their sepulcher inscriptions, giving both the solar Julian date and the corresponding date on the luni-solar Biblical calendar. One such inscription, dated Friday, November 5, 269 C.E. states: “In the consulship of Claudius and Paternus, on the Nones of November, on the day of Venus, and on the 24th day of the lunar month, Leuces placed [this memorial] to her very dear daughter Severa, and to Thy Holy Spirit. She died [at the age] of 55 years, and 11 months, [and] 10 days.”[8]

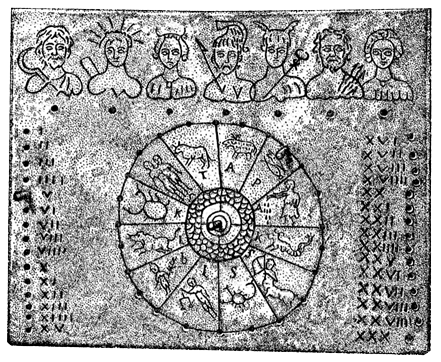

| This stick calendar from the Baths of Titus, constructed in 79 – 81 C.E. shows Saturn, holding his sickle, as god of the first day of the week (Saturday). The sun god is next (Sunday), followed by the moon goddess (Monday) on the third day of the week. |

This was the situation Constantine took advantage of for furthering his political agenda. It was a delicate balancing act that favored the pagan faction more than the Christian. First, he enacted a series of laws that honored the day of the Sun, dies Solis, or Sunday. On the original planetary week, Saturday had actually been the first day of the week. Sunday was the second day of the week and Friday was the seventh day.

The sun, however, was Constantine’s personal symbol. He had Sol Invictus (Unconquered Sun) inscribed on his coins and it remained his personal motto all his life. Exalting Sunday was acceptable to pagans and something on which some Christians had already compromised. By the second century, many Christians (particularly in the west) had already come to revere Sunday as the day of the Saviour’s resurrection. This was the opening Constantine needed for uniting paganism and Christianity.

The Sunday law of Constantine must not be overrated. He enjoined the observance, or rather forbade the public desecration of Sunday, not under the name of Sabbatum [Sabbath] or dies Domini [Lord’s day], but under its old astrological and heathen title, dies Solis [Sunday], familiar to all his subjects, so that the law was as applicable to the worshipers of Hercules, Apollo, and Mithras, as to the Christians. There is no reference whatever in his law either to the fourth commandment or to the resurrection of Christ.[9]

Constantine is viewed as a Christian because of his Sunday law but his “Sunday law” was deliberately ambiguous. He wanted it to be acceptable to both pagans and Christians!

How such a law would further the designs of Constantine it is not difficult to discover. It would confer a special honor upon the festival of the Christian church,[10] and it would grant a slight boon to the pagans themselves. In fact there is nothing in this edict which might not have been written by a pagan. The law does honor to the pagan deity whom Constantine had adopted as his special patron god, Apollo or the Sun. The very name of the day lent itself to this ambiguity. The term Sunday (dies Solis) was in use among Christians as well as pagan.[11]

The seven-day planetary week was the vehicle for change. Both the eight-day Julian week and the seven-day Biblical week were laid aside for the planetary week of Mithraism. This week came from paganism,not the Bible as Christians today assume. “The time was ripe for a reconciliation of state and church, each of which needed the other. It was a stroke of genius in Constantine to realize this and act upon it. He offered peace to the church, provided that she would recognize the state and support the imperial power.”[12]

Constantine’s Sunday law did reconcile pagans and many of the Christians. However, it also served to bring to the forefront a controversy that had already raged for over 100 years: when to celebrate the Saviour’s sacrifice. Up until this time, many Christians, especially in the east, were still worshipping on the seventh-day Sabbath as well as keeping the annual feasts of Yahuah calculated by the Biblical luni-solar calendar. Even many who had embraced worship on Sunday still used the Biblical calendar for calculating Passover.

It was a longstanding debate involving two different calendars.

Since the second century A.D. there had been a divergence of opinion about the date for celebrating the paschal (Easter) anniversary of the Lord’s passion (death, burial, and resurrection). The most ancient practice appears to have been to observe the fourteenth (the Passover date), fifteenth, and sixteenth days of the lunar month regardless of the day of the [Julian] week these dates might fall on from year to year. The bishops of Rome, desirous of enhancing the observance of Sunday as a church festival, ruled that the annual celebration should always be held on the Friday, Saturday, and Sunday following the fourteenth day of the lunar month. In Rome, Friday and Saturday of Easter were fast days, and on Sunday the fast was broken by partaking of the communion. This controversy lasted almost two centuries, until Constantine intervened in behalf of the Roman bishops and outlawed the other group.[13]

A statement by Eusebius of Caesarea reveals that the churches of Asia had long clung to observing Passover on Abib 14, while the churches in the west had transitioned to the pagan Easter Sunday:

A question of no small importance arose at that time [late second century] for the parishes of all Asia, as from an older tradition, held that the fourteenth day of the moon, on which day the Jews were commanded to sacrifice the lamb, should be observed as the feast of the Saviour’s Passover. It was therefore necessary to end their fast on that day, whatever day of the [Julian] week it should happen to be. But it was not the custom of the churches in the rest of the world to end it at this time….[14]

The continuous weekly cycle of the Julian calendar meant that the Biblical Passover on Abib 14 could fall on any day of the Julian week. Consequently, Abib 16, the day of the resurrection, did not always fall on Sunday. Those pressing for an Easter celebration on the Julian calendar drew up a decree, proclaiming that all Christians should observe the resurrection on Easter Sunday, rather than the Passover of Abib 14. Thus, the observation of a pagan holiday ostensibly honoring Jesus’ resurrection supplanted Yahuah’s feast commemorating Yahusha’s death.

Synods and assemblies of bishops were held on this account, and all, with one consent, through mutual correspondence drew up an ecclesiastical decree, that the mystery of the resurrection of the Lord should be celebrated on no other but the Lord’s day [Sunday], and that we should observe the close of the paschal fast on this day only.[15]

Those clinging to Biblical calendation immediately protested the highhanded decree of the western bishops. In a letter sent to Victor, Bishop of Rome, Polycrates declared his firm belief in continuing to use the Biblical calendar for observation of Passover. His letter is of particular importance to Christians today because it lists John the Beloved and the Apostle Phillip as keeping the Passover! Eusebius relates:

But the bishops of Asia, led by Polycrates, decided to hold to the old custom handed down to them. He himself, in a letter which he addressed to Victor and the church of Rome, set forth in the following words the tradition which had come down to him:

We observe the exact day; neither adding, nor taking away. For in Asia also great lights have fallen asleep, which shall rise again on the day of the Lord’s coming, when he shall come with glory from heaven, and shall seek out all the saints. Among these are Philip, one of the twelve apostles . . . and, moreover, John, who was both a witness and a teacher, who reclined upon the bosom of the Lord, and . . . fell asleep at Ephesus. And Polycarp in Smyrna, who was a bishop and martyr . . . All these observed the fourteenth day of the passover according to the Gospel, deviating in no respect, but following the rule of faith.[16]

If the believers in Asia were refusing to give up the Biblical calendar for calculating Passover, it is probable that they had likewise refused to forsake the true Sabbath calculated by the same calendar. The Bishop of Rome “immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them as heterodox; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.”[17]

It is of import to note that there was never any argument over when the resurrection actually occurred. Both acknowledged that it occurred on Abib 16 of the luni-solar calendar. The disagreement, as noted in the quote above, was over when to celebrate it. Dates are established by calendars, so ultimately, it was an argument over which calendar would be used to determine the celebration. In order to truly unify Christians and pagans alike, the observance of the crucifixion and resurrection had to be transferred from the Biblical luni-solar calendar to the pagan, Julian solar calendar. Four years after the decrees exalting Sunday in 321 C.E., Constantine convened the Council of Nicea in 325 to settle this debate.

No longer would the Saviour’s sacrifice be observed on the 14th, 15th and 16th days of Abib on the luni-solar calendar. In the future, such remembrances would be transferred to the Friday, Saturday and Easter Sunday of the Julian calendar, which can drift from March 20-22 to April 22-25. The bishop of Rome, himself desirous of greater power and influence, threw the weight of his influence with Constantine. “By the time of Constantine, apostasy in the church was ready for the aid of a friendly civil ruler to supply the wanting force of coercion.”[18]

Constantine was emphatic that Jewish calendation should no longer be used for calculating these dates.

At the Council of Nice [Nicea] the last thread was snapped which connected Christianity to its parent stock. The festival of Easter had up till now been celebrated for the most part at the same time as the Jewish Passover, and indeed upon the days calculated and fixed by the Synhedrion [Sanhedrin] in Judæa for its celebration; but in future its observance was to be rendered altogether independent of the Jewish calendar, “For it is unbecoming beyond measure that on this holiest of festivals we should follow the customs of the Jews. Henceforward let us have nothing in common with this odious people; our Saviour has shown us another path. It would indeed be absurd if the Jews were able to boast that we are not in a position to celebrate the Passover without the aid of their rules (calculations).” These remarks are attributed to the Emperor Constantine . . . [and became] the guiding principle of the Church which was now to decide the fate of the Jews.[19]

| Constantine accomplished three things, the ripple effects of which resound to this day: 1. Standardized the planetary week of seven days making dies Solis (Sunday) the first day of the week, with dies Saturni (Saturday) the last day of the week. 2. Exalted Easter and guaranteed that the true Passover and the pagan Easter would never fall on the same day. 3. Exalted dies Solis as the day of worship for both pagans and Christians. |

The long-term effect was that “Easter Sunday” entered the Christian paradigm as The Day of Christ’s resurrection. The corollary to this realignment of time calculation was that the day preceding Easter Sunday, Saturday, became forever after The True Bible Sabbath. This is the true significance of Constantine’s “Sunday law” and it laid the foundation for the modern assumption that a continuous weekly cycle has always existed.[20]

The result of Constantine’s actions actually favored the pagan faction of the empire. However, the corrupt bishops of Rome were able to present these actions as favorable to Christians. “By the time of Constantine, apostasy in the church was ready for the aid of a friendly civil ruler to supply the wanting force of coercion.”[21] The true luni-solar calendar, handed down from Creation and Moses, was lost.

The result of Constantine’s ecumenism was swiftly felt. All who refused to give up the use of the Biblical calendar for calculating Passover, felt the heavy hand of oppression fall on them. Constantine’s son, Constantius, took his father’s act one step further and outlawed the use of the Biblical calendar for Jews as well. Historian David Sidersky observed: “It was no more possible under Constance to apply the old calendar.”[22]

In subsequent years, the Jews went through “iron and fire.” The Christian emperors forbade the Jewish computation of the calendar, and did not allow the announcement of the feast days. Graetz says, “The Jewish communities were left in utter doubt concerning the most important religious decisions: as pertaining to their festivals.” The immediate consequence was the fixation and calculation of the Hebrew calendar by Hillel II.[23]

Constantius’ act impacted apostolic Christians as well. While Tertullian[24] reveals paganized Christians were already transferring their worship to the “day of the Sun” as early as the second century, others clung to the true Sabbath for over 1,000 years. Almost 40 years after the Council of Nicea, the Council of Laodicea (c. 363-364) released a statement demanding that Christians work on the Sabbath and abstain from work on the Lord’s day. This decree, translated into English, states:

Christians shall not Judaize and be idle on Saturday, but shall work on that day; but the Lord’s day they shall especially honor, and, as being Christians, shall, if possible, do no work on that day. If however, they are found Judaizing, they shall be shut out from Christ.

According to Roman Catholic bishop and scholar, Karl Josef von Hefele (1809-1893), the use of the word “Saturday” in the above quote is incorrect. In the original, the word used was Sabbath or Sabbato not dies Saturni or Saturday.

Quod non oportet Christianos Judaizere et otiare in Sabbato, sed operari in eodem die. Preferentes autem in veneratione Dominicum diem si vacre voluerint, ut Christiani hoc faciat; quod si reperti fuerint Judaizere Anathema sint a Christo.

Christians at the time of the calendar change were not confused over Saturday being the Sabbath. Everyone knew that dies Saturni had recently been moved from the first day of the pagan, planetary week to the last day . . . while Sabbato was the seventh day of the Jewish luni-solar calendar with which no one in power wished to be associated. Again, these were two different days on two distinct calendar systems.[25]

The political power of Rome lent support to the religious decrees of Constantine and Constantius. While some scholars have mistakenly assumed that the conflict was over Saturday versus Sunday, the historical reality reveals that people of the time were well aware of the existence of the Biblical luni-solar calendar and how to use it. Many believers in the east or beyond the reaches of the Roman Empire were loathe to abandon Biblical time-keeping. “Those Christians who were looking for a way out of their difficulty with Sabbath observance moved towards a greater regard for the first day of the [Julian] week. But others on the outskirts of the Empire, where anti-Semitism did not exist, continued their veneration of the seventh day Sabbath.”[26]

REACTION

Hillel II

Just as Constantine was the power behind an action that ultimately led to the destruction of the Biblical calendar for use by Christians, another man, a Jew, was responsible for a reaction that had consequences just as far reaching.

| “Declaring the new month by observation of the new moon, and the new year by the arrival of spring, can only be done by the Sanhedrin. In the time of Hillel II, the last President of the Sanhedrin, the Romans prohibited this practice. Hillel II was therefore forced to institute his fixed calendar, thus in effect giving the Sanhedrin’s advance approval to the calendars of all future years.” “The Jewish Calendar and Holidays (incl. Sabbath): The Jewish Calendar: Changing the Calendar,” http://www.torah.org. |

Prior to the destruction of Jerusalem, the High Priest had been in charge of the calendar. “While the Sanhedrin (Rabbinical Supreme Court) presided in Jerusalem, there was no set calendar. They would evaluate every year to determine whether it should be declared a leap year.”[27] This task fell to the president of the Sanhedrin when the priesthood was no more. “Under the reign of Constantius (337-362) the persecutions of the Jews reached such a height that . . . the computation of the calendar [was] forbidden under pain of severe punishment.”[28] It was as a reaction to this situation that Hillel II, President of the Sanhedrin, took the extraordinary step in 359 C.E. of modifying the ancient Biblical calendar to allow the Jews to more easily coexist with the Christians.

After Hillel II

Distant communities would no longer have to wait for messengers from the President of the Sandedrin to reach them to know when a new month had started. Each community would henceforth be able to determine for themselves when a new month began and when a 13th month was to be added.

The “Fixed” Calendar

When Hillel II “fixed” the calendar, he incorporated leap years on a permanent basis.[29] It is possible, but not provable, that this particular cycle of leap years was used and understood prior to Hillel as it follows the 19-year metonic cycle. Hillel based his calendar “on mathematical and astronomical calculations [rather than observations]. This calendar, still in use, standardized the length of months and the addition of months over the course of a 19 year cycle, so that the lunar calendar realigns with the solar years.”[30] He declared a thirteenth month to be intercalated in the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 11th, 14th, 17th, and the 19th years of the 19-year cycle.

But Hillel did more than make known a 19-year cycle of intercalations that was, in all probability, used all along. He also transferred the observance of the ancient Sabbath from the 8th, 15th, 22nd and 29th days of the lunar month, to every Saturday of the Julian months. This change necessitated still another: rules of postponement. Changing the weekly Sabbath from the luni-solar calendar to Saturday is clearly implied by the need for rules of postponement which, prior to Hillel’s “fixing” of the calendar, had been unnecessary. According to the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, “The New Moon is still, and the Sabbath originally was, dependent upon the lunar cycle.”[31] When both the Sabbath and the annual feasts are calculated on the luni-solar calendar, rules of postponement are unnecessary. It is only when the yearly feasts are calculated by one calendar, and the weekly Sabbath is calculated by another, that there are conflicts requiring rules of postponement.

| Rules of Postponement 1. The Jewish New Year, Feast of Trumpets, may not fall on Sunday, Wednesday or Friday. 2. If the New Moon (molad) for the seventh month falls on Sunday, Wednesday or Friday, the New Moon is postponed until the following day. 3. If the molad of the seventh month in a common year occurs on Tuesday at 3:204/1080 A.M. or later, the New Moon is postponed until Thursday. 4. In a common year following a leap year, if the molad of the seventh month occurs after 9 a.m. and 589/1080 parts on a Monday morning, New Moon is postponed until Tuesday. |

Without the rules of postponement, the annual feasts come into conflict with Saturday. For example, if Feast of Trumpets (New Moon for the seventh month) were to fall on a Sunday, the last day of Feast of Tabernacles would fall on a Saturday, conflicting with the traditional observance for the last day of the feast. Hence the need for the first and second rules of postponement. The third rule of postponement insures that the common year in question would not be longer than 355 days. The fourth rule of postponement guarantees that a common year following a leap year is not shorter than 383 days.[32]

This “fixed” calendar is highly regimented.

There are exactly fourteen different patterns that the Hebrew calendar years may take, distinguished by the length of the year and the day of the week on which Rosh Hashanah falls. Because the rules are complex, a pattern can repeat itself several times in the course of a few years, and then not recur again for a long time. But the Jewish calendar is known to be extremely accurate. It does not “lose” or “gain” time as some other calendars do.[33]

This was an act of survival by Hillel II. It was made in response to the brutal persecutions of Constantine’s son, Constantius.

With his own hand the Patriarch destroyed the last bond which united the communities dispersed throughout the Roman and Persian empires with the Patriarchate. He was more concerned for the certainty of the continuance of Judaism than for the dignity of his own house, and therefore abandoned those functions for which his ancestors . . . had been so jealous and solicitous. The members of the Synhedrion favored this innovation.[34]

When Hillel II “fixed” the calendar, he, in his position as President of the Sanhedrin, effectually gave permission to the Jews to worship on Saturday for all future time.

| Result Today, nearly 1700 years later, the action of Constantine and its resulting reaction by Hillel II, are still impacting hundreds of millions of people around the world. • Catholics worship on Sunday in honor of the resurrection. This is in accordance with the act of Constantine which changed the observance from a luni-solar calculated Passover to the pagan, solar calculated Easter. • Jews worship on Saturday because Talmudic law justifies the act of keeping one day in seven when one does not know when the true Sabbath falls. • Most Protestants join with Catholics in worshipping on Sunday, the first day of the modern, Gregorian week, assuming it is the day of the resurrection. • Saturday-sabbath keeping Protestants worship on Saturday because it is the seventh-day of the modern week and they assume that since the Jews worship on Saturday, it must be the Biblical Sabbath. • Muslims, likewise, honor the pagan/papal Gregorian method of calendation by going to mosque for prayers on Friday. |

It is not possible to find the true seventh-day Sabbath using the modern Gregorian calendar. This solar calendar is nothing more than a pagan method of time calculation. The early Julian calendar was established by pagans, for pagans. It was officially adopted for ecclesiastical use at the Council of Nicea. It was later adjusted by Jesuit astronomer, Christopher Clavius, at the behest of Pope Gregory XIII – hence the name, Gregorian calendar. Clavius confirmed that the Julian calendar (and thus the Gregorian calendar that comes from it) is founded on paganism and has no connection whatsoever to the Biblical calendar.

In his explanation of the Gregorian calendar, Clavius admitted that when the Julian calendar was accepted as the ecclesiastical calendar of the Church, the Biblical calendar was rejected: “The Catholic Church has never used that [Jewish] rite of celebrating the Passover, but always in its celebration has observed the motion of the moon[35] and sun, and it was thus sanctified by the most ancient and most holy Pontiffs of Rome, but also confirmed by the first Council of Nicaea.”[36] The “most ancient and most holy Pontiffs of Rome” here spoken of refer to the pagan College of Pontiffs of which Constantine, as Pontifex Maximus, was the head.

Constantine desired unity. He achieved this goal through ecumenism and outlawing the use of the Biblical calendar for remembering the death of Yahusha. Hillel II desired the physical survival of Judaism. He achieved his goal by compromising with paganism and modifying the Biblical calendar. The result of this action and it’s accompanying reaction has been the assumption by multitudes that Saturday is the Biblical Sabbath and Sunday is the day on which the Saviour was resurrected. Thus, Christians and Jews have calculated their worship days using pagan solar calendation, neglecting the true Sabbath of Yahuah.

None who desire to worship the Creator on His holy Sabbath will calculate their worship days by this abomination of desolation that dishonors Yahuah and desolates the soul. Only the luni-solar calendar of Creation can pinpoint when the true Sabbath occurs. Lay aside the traditions of man. Accept only the word of Yah and worship Him by His ordained method of time-keeping.

Bibliography (Reference List):

[1] This title, now claimed by the pope, comes from ancient Rome. The Pontifex Maximus was the high priest of the College of Pontiffs of the pagan Roman religion. It was both a religious as well as a political office.

[2] New Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, pp. 179-181. Various inscriptions as recorded in Corpus Inseriptionum Latinarum, 1863 ed., Vol. 2, p. 58, #481; “Constantine I”, New Standard Encyclopedia, Vol. 5. See also Christopher B. Coleman, Constantine the Great and Christianity, p. 46.

[3] See Robert L. Odom, Sunday in Roman Paganism, “The Planetary Week in the First Century B.C.”

[4] P. Brind’Amour, Le Calendrier romain: Recherches chronologiques, 256–275.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_calendar#Nundinal_cycle

[6] Eviatar Zerubavel, The Seven-day Circle, p. 46, emphasis supplied.

[7] Franz Cumont, Textes et Monumnets Figures Relatifs aux Mysteres de Mithra, Vol. I, p. 112, emphasis supplied.

[8] E. Diehl, Inscriptiones Latinae Christianae Veteres, Vol. 2, p. 193, No. 3391. See also J. B. de Rossi, Inscriptiones Christianac Urbis Romae, Vol. 1, part 1, p. 18, No. 11.

J. B. de Rossi,

[9] Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol. III, p. 380, emphasis supplied.

[10] By this time, the paganized Christians in the west had long been venerating Sunday as the day of Yahusha’s resurrection.

[11] J. Westbury-Jones, Roman and Christian Imperialism, p. 210, emphasis supplied.

[12] Michael I. Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, p. 456.

[13] Odom, op. cit., p. 188, emphasis supplied.

[14] Eusebius, Church History, Book V, Chapter 23, v. 1, emphasis supplied.

[15] Ibid., v. 2.

[16] Ibid., Chapter 24, v. 1-4, 6, emphasis supplied.

[17] Ibid., v. 9.

[18] Michael I. Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, p. 456.

[19] Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews, (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1893), Vol. II, pp. 563-564, emphasis supplied.

[20] eLaine Vornholt & Laura Lee Vornholt-Jones, Calendar Fraud, “Biblical Calendar Outlawed,” emphasis supplied.

[21] Rostovtzeff, op. cit., p. 456.

[22] David Sidersky, Astronomical Origin of Jewish Chronology, p. 651, emphasis supplied.

[23] Grace Amadon, “Report of Committee on Historical Basis, Involvement, and Validity of the October 22, 1844, Position”, Part V, Sec. B, pp. 17-18, Box 7, Folder 1, Grace Amadon Collection, (Collection 154), Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan.

[24] Tertullian,Apologia, chap. 16, in J. P. Migne, Patrologiæ Latinæ, Vol. 1, cols. 369-372; standard English translation in Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 3, p. 31.

[25] Vornholt, op. cit., “Changing the Calendar: Papal Sign of Authority.”

[26] Leslie Hardinge, Ph.D., The Celtic Church in Britain, p. 76. Christians in Scotland continued to calculate Passover by the Biblical calendar until they got a Roman Catholic queen in the eleventh century.

[27] http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/526875/jewish/The-Jewish-Year.htm

[28] Excerpted from The Jewish Encyclopedia, “Calendar, History of,” http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/3920-calendar-history-of, emphasis supplied.

[29] For an explanation of how the rabbinical calendar of Hillel II is calculated, see http://www.jewfaq.org/calendr2.htm.

[30] Judaism 101, “Jewish Calendar,” www.jewfaq.org

[31] Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, “Holidays,” p. 410.

[32] http://www.ironsharpeningiron.com/postponements2.htm

[33] http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/526875/jewish/The-Jewish-Year.htm

[34] Graetz, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 573.

[35] “Easter is a moveable feast, which means that it does not occur on the same date every year. How is the date of Easter calculated? The Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) set the date of Easter as the Sunday following the paschal full moon, which is the full moon that falls on or after the vernal (spring) equinox.” (http://catholicism.about.com/od/holydaysandholidays/f/Calculate_Date.htm)

[36] Christopher Clavius, Romani Calendarii A Gregorio XIII P.M. Restituti Explicato, p. 54.

Source of the Article: https://www.worldslastchance.com/